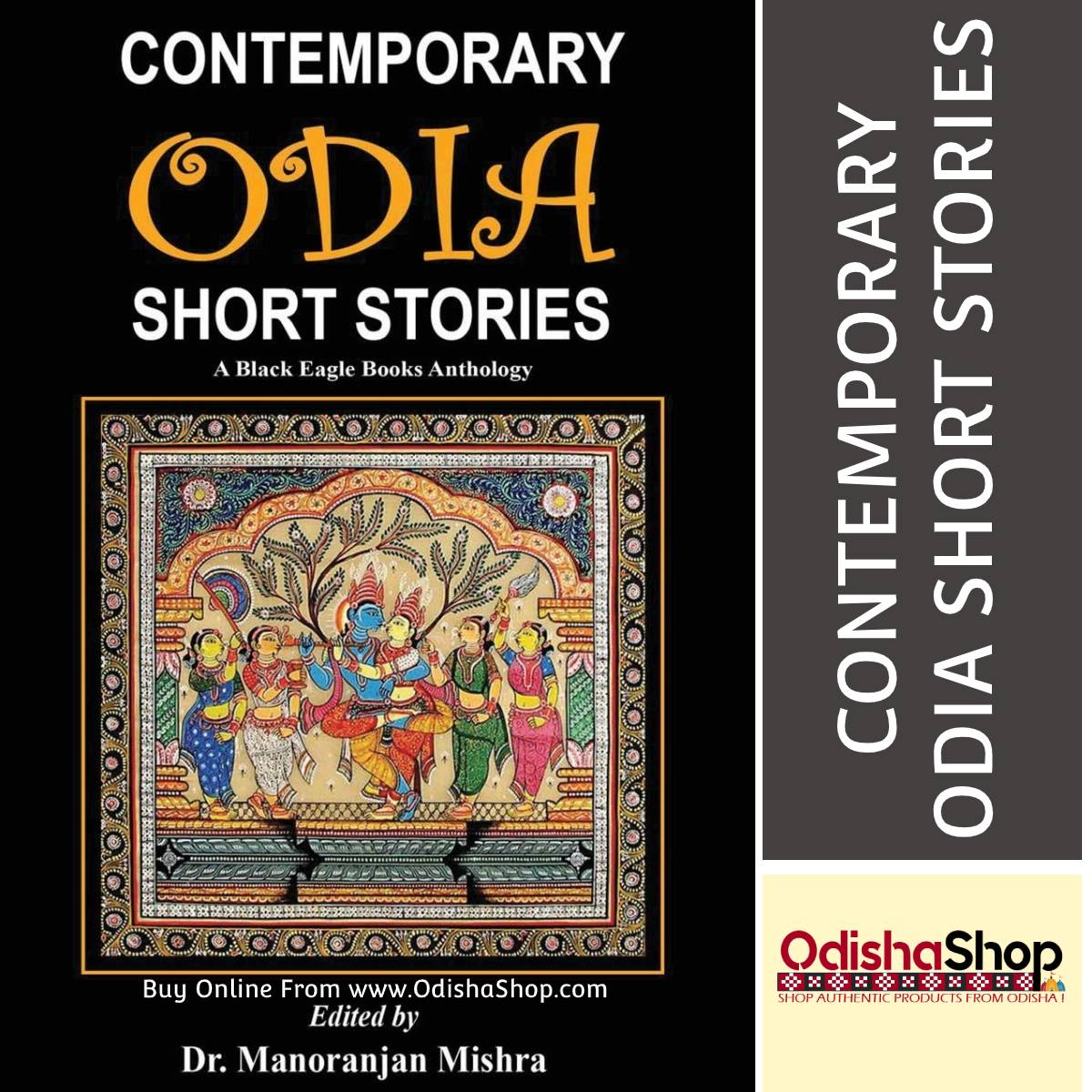

Description

Manoranjan Mishra

Translated by Supriya Kar

Translated by Supriya Kar

Translated by Manoj Das

Translated by Manoranjan Mishra

Translated by Rajat Mohapatra

Translated by Saroj Mishra

Translated by Sunita Mishra

Translated by Bikram Das

Translated by Gopa Nayak

Translated by Rabindra Kumar Swain

Translated by Lipipuspa Nayak

Translated by Gopa Nayak

Translated by Bhagaban Jayasingh

Translated by Sulagna Mishra

Translated by Satya Misra

Translated by Manoranjan Mishra

Translated by Bikram Das

Translated by Snehaprava Das

Translated by Lipipuspa Nayak

Translated by Manoranjan Mishra

Translated by Manoranjan Mishra

Translated by Saroj Mishra

Translated by Kamala Prasad Mahapatra

Translated by Chinmay Kumar Hota

Translated by Snehaprava Das

Translated by Adyasha Das

Translated by Manas Panda

Translated by Pravat Kumar Mallick

Translated by Sabahat Tabriz

Translated by Tarun Kumar Sahoo

Translated by Manoranjan Mishra

Fakir Mohan Senapati laid the foundation of Odia short stories with the publication of ‘Rebati’ in 1898, about a hundred and twenty two years ago. Ever since, the genre has evolved much. He wrote about twenty short stories between 1898 and 1916. Critics have accepted this phase as the first phase of Odia story writing. Some contemporaries of Fakir Mohan who rose to prominence during that period are Chandra Sekhar Nanda, Dayanidhi Mishra, Dibyasingha Panigrahi and Laxmikanta Mohapatra. The writers raised a voice of protest against the blind beliefs prevalent in the society. Compassion for the poor and the exploited, voice of protest against the exploiters, love and romance in the lives of the common people, real life incidents and the writer’s own reaction to those were the subject matters of the stories written during that period.

The period between 1910 and 1947 is known as the second phase in the life of Odia short stories. This was the period when realism, progressive thoughts, Gandhian ideals, Marxism, the freedom struggle etc. had their impacts. The story writers were guided by an instinct to reform the society, serve people and help in promotion of nationalistic feelings. The conflict between the capitalists and the bourgeois class was represented, with the story writers showing compassion for those who suffered. They also raised fingers at social evils and economic disparity. Gadhian thoughts and socialism had their say too. During this period, the writers who made remarkable contributions to the field are Godabarisha Mishra, Godabarisha Mohapatra, Kalandi Charan Panigrahi, Baikunthanath Pattanaik, Bhagabati Charan Panigrahi, Sachidananda Routray etc.

The period between 1947 and 1960 is known as the next phase. The much awaited independence not only impacted the social life but also the economic and political life of the people. The zamindari system was abolished. Education reached the masses. Accumulation of money and power became the two guiding principles of politics. The number of middle class people increased, resulting in large scale unemployment. People flocked cities that were raising their heads but they had to encounter various troubles there. Struggle of the individual gained superiority over the class-struggle. The devastated economy and collapse of morality crippled the nation. Joint family system broke down. Women received education, gained employment, and started demanding equal rights. Morality, spirituality, tradition, conservative attitude—all these went for a toss. As a result, feelings of disappointment and helplessness took over. Existentialism also impacted Odia stories. The stories written during this period reflect all these elements. The writers who contributed immensely during this period are Rajkishore Ray, Rajkishore Patnaik, Pranabandhu Kar, Bama Charan Mitra etc.

After the 1960s, writers started delving deep into the subconscious state of mind and analyzing it minutely. Besides, a period of ‘quest’ or ‘search for knowledge’ ensued. The writers were more serious about their quest into life, world, death, sorrow and suffering. This was a phase when the conservative mindset was set aside. This apart, many movements like ‘Humanism,’ ‘Socialism,’ ‘Existentialism,’ ‘Symbolism’ etc. took the writers into their grips. ‘Sex’ which was hitherto a concept to be discussed in bedrooms, came to be discussed openly. This gave a serious jolt to the conservative mindset. Imagination came to be replaced by real life experiences. With the world shrinking into aa global village, how could Odia short story writers remain unaffected by changes taking place in other parts of the world?

The present anthology has thirty-one Odia stories translated into English. Each story gives a new taste in so far as treatment of the subject matter and style are concerned. We have past masters who have carved a niche for themselves. More than half of our writers have been conferred on either the Odisha Sahitya Akademi award or the Central Sahitya Akademi award or both. We also have new talents who are venturing to touch the sky.

The writers who gained prominence during the period from 1960 to 1980 and whose translated stories have been included here are Achyutananda Pati, Santanu Kumar Acharya, Manoj Das, Binapani Mohanty, Ramachandra Behera, Padmaja Paul, Satya Misra, Yashodhara Mishra, Bibhuti Pattanaik, Debraj Lenka, Banaj Devi, Radha Binod Nayak, and Archana Nayak. The writers who shot to prominence during 1980 to 1990 are Dash Benhur, Tarunkanti Mishra, Prativa Ray, Hrusikesh Panda, Paresh Patnaik, Manoj Panda, and Bibhuti Bhusan Pradhan. Similarly, the writers who reigned the world of Odia stories during 1990 are Gourahari Das, Gayatri Saraf, Dipti Ranjan Patnaik, Supriya Panda, and Paramita Satapathy. The emerging talents whose stories have been included in the anthology are Adyasha Das, Kshetrabasi Naik, Manas Panda, Rabinarayan Dash, Sreekanta Kumar Barik, and Ranjan Pradhan.

This anthology is a product of the laudable efforts of Satya Pattanaik and his Black Eagle Books to propagate Odia literature and present a bouquet of stories in translated from both to the Odia readers residing in different parts of the globe as well as to the global readers interested in Odia literature. It’s true that all great writers of the past and all great works have not been given space in this anthology. But, it’s also true that we have just made a beginning. We dream of undertaking many such ventures in the days to come. For the dreams to turn into reality, cooperation of writers, copyright holders, as well as translators is highly solicited.

Let’s undertake a short journey through the stories we have selected for you.

Achyutananda Pati’s Tale of an Ominous Son has an impatient, insistent, and rebellious owl fledgling as the protagonist. Disregarding his mother’s advice, ‘We must live in darkness. Otherwise, we’ll perish,’ he dreams of a world where light reigns. He is not ready to accept that he is the member of an ominous species and a curse on the world. He is always ready to challenge the children of light who hang around the realm of light to victimize them. He wages a war against them. Before death he tells his mother never to feel ashamed of his death but rather inform his siblings that he became a ‘martyr fighting valiantly to win the kingdom of light.’

Santanu Acharya’s The Living God deals with the mysterious disappearance of a five-year-old Miskun, who along with his parents and uncle is on a tour of some heritage sites in Bhubaneswar. After touring through Kedargouri, Mukteswar, Rajarani, Lingaraj temples and the State Archaeological Museum they decide to have lunch at Hotel Kalinga Ashok. It is from here that Miskun suddenly disappears. A frantic search ensues. Seema, Miskun’s mother, wails out the names of gods and goddesses to help her trace out her son. This invocation works. Moments later, Miskun is discovered sitting in a lotus posture behind a Buddha sculpture. He is found saying, “I’m not a dead god! No, you can’t sell me—you can’t sell me!” The entire incident remains shrouded in mystery.

The world might teach us a lesson in ‘helplessness’ anytime; we should never make fun of others’ helplessness. With his characteristic touch of humour, Manoj Das in Night in the Life of the Mayor describes how Mayor Divyasimha learns the lesson the hard way. The Mayor comes to the riverbank one evening to enjoy the cool and quiet moments of sunset. It is then that he is infused with the desire to ‘plunge his bathroom conditioned body into the free transparent flow’ of the river. He takes off his clothes except the underwear and dashes into the water. Just when he comes out of the water, under the cover of darkness, he marks an apparition swaying between the water and the embankment. It is a cow, known for its notoriety. It had munched away his shirt and part of the trousers. The mayor remains inside water. On the other hand, his long absence necessitates searches by his colleagues, police and family members. Every time people come close to him, he moves deeper into water, ashamed to expose himself. He floats downstream in the current of water and reaches a boat. The next morning, he is helped by a fisherman and his daughter, who help him with clothes. He returns to the town but not without learning a lesson.

Binapani Mohanty’s Patadei is a strong slap on the faces of the representatives of the patriarchal society who leave no stones unturned to scandalize women. All fingers are raised on Patadei when she returns from her in-laws house a few months after marriage. Everybody gets an opportunity to cast aspersions on her. When she disappears suddenly on the Dola Purnima night, tongues wag again. When she returns years later, with a child in her arms, how can the villagers lose a God-given opportunity to victimize a woman? The truth is finally revealed. Her husband had left her for another woman only a few days after marriage. On the night of Dola Purnima, she was brutally raped by some young men of the village. Haria Bauri, a villager, bribed by the culprits, had dropped her at Cuttack the next day. The revelation forces her accusers to hang their heads in shame.

‘Just as a society has no respect for an honest man if he has no money, a family never ever cares for one who did not earn.’ Freedom fighter Naran Das in Bibhuti Pattanaik’s A Pair of Parallel Lines realizes this towards the fag end of his life. Naran Das and his son Sanatan were like parallel lines; they lived under the same roof but there was hardly anything common between them. A morally upright person, Das, never took advantage of his role in the freedom struggle for materialistic or other gains after independence. On the other hand, his son became a misguided young man with a penchant for easy money. He took to boozing. He wanted to use his father for personal gains. The chasm between Das and his family members increased as he ‘had never learned the act of bartering his selfless sacrifice of the past for personal comforts on the present.’

The Music of Life by Debraj Lenka is a pathetic account of a father, who loses his only son in a freak accident. The dreams of the poor but hardworking father are shattered. Raghu Pradhan’s master owned vast tracts of land. Raghu was in charge of tilling, harvesting, and storing the grain. Besides, he weighed the paddy, carried it to the sellers in the city and collected cash from them. Despite his hard work, he got a pittance. Although the store houses were overflowing with grain, Raghu hardly had enough to feed his family. Only when his son grew up and worked with him, they would have plenty of food to eat. Just when he was lost in such a dream, his son fell off the cart, rolled under it, and was dragged under its wooden wheels. Moments later, he died. In order to avoid harassment by police, he disposed off the body into a river. He had to return home, cursing his fate.

‘Your wooden son (Lord Jagannath) is great. If you surrender to him, he doesn’t give you prosperity. But, he guards you diligently in the path of love and compassion.’ Chandu, a constable, learns this lesson while performing his duty in Banaj Devi’s The Wooden Son. The heart of Chandu is filled with intense grief and compassion the moment he gets an order to carry out an evacuation. On the eve of the evacuation, he proceeds to the slum intending to convince people to vacate in time and prevent bloodshed. He is misunderstood. He returns on being pushed around by the slum dwellers. However, the condition of some of the slum dwellers moves him a lot. During the evacuation process, when the bulldozers roar on over the helpless shrieks and cries, leaving behind rubble of bricks, torn tarpaulins, and broken bamboo, Chandu drags two women out of their sacks and saves their lives. He also shields a pregnant woman from being lath charged. Chandu is badly bruised in the process; he could even lose his job on charges of non-performance of duty. But, he is found beaming with a strange satisfaction as his wooden son had guided him in the right path.

Bidhan Sir, the protagonist of Pratibha Ray’s Adoration, worshipped sandals of his uncle, much like Bharat of The Ramayan. When many an eyebrow was raised, he explained that he did so not only as a mark of respect and adoration for what his uncle had done for him but also as a penance for having forgotten to buy a pair of sandals for uncle at the right time. As Bidhan’s father was very strict, Bidhan grew closer to his uncle. His uncle loved Bidhan more than he loved his own son. During the scholarship examination in class seven, uncle would carry him on his shoulders for about a month, growing blisters on his feet. When Bidhan stayed in the hostel for his higher studies, his uncle would carry rice, ghee, jaggery, coconut from the village. On his deathbed, Bidhan’s uncle wished to have a pair of sandals. Bidhan suddenly remembered that he had forgotten to bring him a pair although he had promised him earlier. When he finally bought him a pair, uncle became so elated that he didn’t take them off till he died. After his death, Bidhan carried the sandals home as a relic and worshipped them as a fond remembrance.

The Torn Edge of the Saree by Archana Nayak is a tale of guilt, remorse and repentance. Surama, a housewife and successful literary personality, goes to attend a felicitation ceremony, leaving behind Bilu, her pet dog on his deathbed. She had brought Bilu home when he was only ten days old. She had faced a great deal of difficulty in taking care of such a small dog. However, with the passage of time, her love for the dog had grown. Even though she was present at the felicitation ceremony, her mind was constantly diverted towards Bilu and his condition. It was as if Bilu was asking him, “Maa, you left me and went away. Didn’t you realize that I was not going to live any longer? What was so important that you left me in this condition and went away?” By the time she came back, Bilu had already died. Towards the end, he had been frequently looking for Surama. He died when the domestic help brought a saree and covered him with its ends. Surama is filled with a sense of guilt and regret for having abandoned a dying animal for a mere literary award.

Temporary Address by Ramachandra Behera is about a poor, helpless father whose nine year old daughter, Jolly goes suddenly missing and remains untraceable. Jolly, one afternoon, was sent to buy some grocery but disappeared mysteriously. Sambhu brought the matter to knowledge of Shantanu, a local leader, who promised to help. The police officers, on being informed, conducted enquiry but it remained inconclusive. After a few days, the bag and bottles of Jolly are recovered from a bridge about a kilometer away but there is no trace of Jolly. ‘The incident that had created a ripple and moments of excitement, was forgotten like other such incidents. The daughter remained mysteriously missing and un-traceable.’

The narrator in Radha Binod Nayak’s Village During Winter had lived peacefully in the city for twenty years, snapping all his ties with his village, where he was born. One evening, a person named Panunath visits him. After prolonged conversation with the narrator, he invites him to visit his village, which he had left after the death of his mother. The next day, the narrator takes a bus and reaches his village in the evening. Panunath informs him many of the former people had passed away. The old patriarch of the Sahu family was counting days. The narrator meets his father and other members of his family after long. Later, he visits the Sahu family. The pathetic condition of the old patriarch moves him deeply.

Giridhari in Padmaja Paul’s Witness attends a court session as a witness in a murder case. He requests the judge to fix another date for the hearing. He had come to the court for the first time and was feeling nervous in the presence of so many lawyers. Back home, when his wife asks for an explanation for his conduct, he reveals that a couple of days back some hooligans had surrounded him and warned him not to be a witness. They had also warned him of dire consequences if he participated. When Giridhari’s wife learns that he had refused to depose owing to fear, she flies into a rage. She accuses him of not thinking about virtue and deserting a person whose son was brutally murdered in broad daylight. She condemns her husband for giving in to fear and wavering from truth. She bangs her hands on the floor, breaking all her bangles. Giridhari is left stunned.

The journey of life is to be completed somehow; it can’t be abandoned midway simply because nobody agrees to accompany us further or because the pathway seems too difficult to tread on. Manju in Tarunkanti Mishra’s The Pathway lives with her ailing grandfather. ‘She couldn’t possible remember the face of her mother or father; she didn’t know whether the paralytic man lying in the next room would be alive tomorrow. There was no knowing if she would continue in her temporary job next month.’ Though her life is beset with troubles, she is hardly ready to surrender and succumb. She is ready to put up a fight, face the situation as it comes, undeterred. When her friend Jajati, who visited her at times, informs her that he would not be able to meet her for an indefinite period, she doesn’t lose her cool or become nervous. ‘She could see how lonely she was and realize how complete she was in her aloneness.’

The Picture Within by Yashodhara Mishra presents Amita, the only lady doctor in a small hospital. The people of the small town and the nearby tribal villages who come to the hospital carry their aspects of life, personal problems in addition to their illness. Once a tribal couple visits her for an abortion. The husband claims that he had already undergone an operation and hence he could never father the child. His wife claimed that his operation had probably failed. The husband wanted the pregnancy to be aborted whereas the woman accused him that he wanted to kill her in the name of abortion. Finally, when the woman gets ready for the abortion, the husband pleads the doctor not to go ahead saying, ‘Let the child live. Let it be born. I forgive her this time.’ The man was proud that he was the master of the house, and hence, he should overlook a few mistakes of the woman once in a while.

The protagonist of The Avenger by Satya Misra is a female cat, who tries to express the agony of her heart, as a tomcat had devoured all three of her little kittens. All she needed was an audience and some compassion. The owner of the house where she lived and his children do not give her a decent hearing although her heart bleeds with unspoken agony. She wants to narrate her agony to the tomcat thinking that he would understand what villainy he had perpetrated, but he only says ‘Oh!’ and goes away, pretending as if he is not the culprit. Just then, she finds a cute mouse and starts narrating it her pathetic experience. Slowly, she pierces the soft body of the mouse with her talons, tears it apart, and pulls the innards out just as the tomcat had done with her children. She finally avenges their death.

For Gayatri, the protagonist of Dash Benhur’s Keeping Words Company, words were troublesome. ‘Their constant badgering had turned into a form of persecution’. Life, for Gayatri had been a torment. A textile engineer by qualification, Gayatri falls in love with Sunand, a journalist-poet with an MA degree in Odia. Both of them separate when one day, suddenly Sunand decides to withdraw his hand. With necessary support not coming from Sunand’s family, Gayatri returns to her father. She starts a brand of T-shirts christened ‘Black One’. Each t-shirt was to be hand woven. The front was to be embroidered—some in Sambalpuri designs and some others in Pipili appliqué work. On the back of each a traditional Odia song or proverb or couplet was to be printed. The lines come to her in dream but those were lines written for her by her poet-husband Sunand. After a chance-meeting with Sunand, Gayatri found “Words had been pursuing her like swarms of insects drawing blood, tugging at her clothes, surrounding her on all sides. Some stroked her lovingly; others pricked her with needles.’ Gayatri decided not to consider words her enemies but let them be what they are.

The Story of the Gypsy Fish by Manoj Panda is the tale of an old, black fish that wanders aimlessly in a bottomless ocean. It neither bothers to make friends nor to be a member of any school. It bears no grudge against anybody or anything. One day, four dark-brown coloured fish attack him and tie him up. They enquire about his family members. They allege that they had taken a huge advance but hadn’t turned up for work. The old fish understands that they were brokers involved in unlawful dispatching of labourers. The old fish got an opportunity to escape after about ten days. After two days of continuous swimming, he reaches an unfamiliar patch in the ocean, a ‘beautiful dreamlike place shimmering brightly in the light of dazzling pebbles, like a park resplendent with colourful lights.’ The old fish later comes to learn that his family was tortured the most in the hands of the fish-mafia bosses. After finding his dead wife, he lets out a wild wail and speeds away.

Hrusikesh Panda’s Reba is different from Rebati of Fakir Mohan Senapati. Rebati’s desire for education, in Fakir Mohan, was thought to be the cause of all suffering. Panda’s Reba is highly educated. She is the first MSC in not only her village but also several villages around. She later goes on to acquire a PhD degree. She even goes to USA to carry out research. She is appointed as a teacher in a university there. The problem with Reba is her feeling of loneliness and helplessness. The village where she spent her childhood days had lost its charm. Lilies didn’t bloom anymore, the village cremation ground had been encroached upon, and the community culture hall had been embroiled in many litigation. The feelings haunted her even in America. Despite her busy schedule, she often felt lonesome. It is this deep, cold, and complex feeling that bothers her.

Gayatri Saraf in her story A Disconcerting Truth believes “Adversities can change the nature of man”. The story is about a class ten student, Leena, who throws into wind the rules, regulations, and norms of discipline of the school and elopes with her boyfriend, who had impregnated her. The strict, disciplinarian headmistress, Aradhana is pained to see the norms set by her shattered like this. Taking the moral responsibility, she informs Leena’s father about her elopement. She expects a broken, helpless father standing before her. Contrary to her expectations, Leena’s father appears nonchalant. Aradhana takes some time to understand that behind the façade of cruelty and carelessness lurked a father’s helplessness. He had not been able to marry his two other daughters off due to various reasons. Aradhana, herself a mother and a lady with a compassionate heart finally wishes, “Leena should marry the young man of his choice and lead a happy life. His boyfriend should not hand her over to a pimp. She should not be abused as a child-bearing-machine. Let her live in peace.”

“No Rudrapratap can ever annihilate love and freedom from the surface of the earth. Meghna will be reborn; she will love poetry; she will love plays. The deceitfulness of all Srikants will come to a big nought in comparison to her deep faith.” Invincibility of love is the central theme of Supriya Panda’s story Backbone. Meghna, the heroine finds herself madly in love with industrialist Rudrapratap’s son, Srikant. Class stands as a barrier between the union of the two. Besides, Srikant fails to undertake the promised revolt against his autocratic father. Finally, Srikant gets married to Tanu, daughter of a friend of his father, an equal in class and status. With the passage of time, Srikant forgets his earlier love. A heart reverberating with the cry “Sky is the Limit” replaces his loving heart. One day, he comes to learn that it was his father’s goons who had abducted Meghna and left her bedridden. His father’s instructions had led to the removal of Purbi, Meghna’s sister, from the theatre group where she was employed. Although driven to penury, Purbi had been struggling to turn her sister from a ‘spineless creature’ to a ‘human being’ who could stand erect with the support of her backbone.

Bibhuti Bhusan Pradhan’s The Home of the Butterfly presents a growing up girl Maanu’s normal day-to-day desires, the non-fulfillment of those in view of the restrictions imposed by a step-mother, the helplessness of a father who unsuccessfully tries to strike a balance, and finally, Maanu’s realization of her father’s helplessness. Maanu’s school hostel closes for vacation. Other students leave one by one but her father doesn’t arrive in time. Maanu, though not initially, but at the end realizes that if she reaches home her father would have to encounter problems like “a disconcerting atmosphere, hurling of things, cassation of cooking” caused by her step-mother. Maanu realizes that her father bears all the torture for her sake. She also understands that behind the façade of the calm and cool appearance that her father presented, there lurked an unfathomable grief for not having done her justice. “No matter how unruffled an appearance he tried to maintain, his inner being was tormented by an incessant storm.” What is striking is Maanu’s way of solving the problem, like a mature person. “The Board Examination is only two months away. I’ll not leave for home. Matron Madam has assured to take care of my food.” Maanu’s actions garner much respect in the minds of the readers for her.

Kanhu in Kanhu’s Home by Gourhari Das, is a sixteen year old boy who comes to the city from Nayagarh in search of work, as his mother finds it difficult to provide for his enormous appetite. The mistress of the house employees him to supervise and guard the newly-constructed house. Smart, diligent, and affectionate, Kanhu not only protects the construction materials but also supervises the works of masons and labourers. He believes in the words of the mistress who says after the construction is completed, he will be given a room and he can bring in his mother to stay with him. However, when he comes back to the city after a visit to his home town, the greatest shock of his life awaits him. The owner of the house had not only let out the house but had also left for Delhi. Kanhu feels cheated.

Abinash, in Paresh Patnaik’s Goodbye, God, receives the greatest jolt of his life when one night he receives a call from ‘God’. Thinking it to be a prank by a friend, he disbelieves the caller at first but a series of events over the next few days convinces him. On being incited by God, he asks for boons. These boons are fulfilled, no doubt, but he has to pay a price every time. Finally, he blurts out, “If I ask for a job now, you will inflict on me torture along with the job. If I ask for eternal bliss, it will be accompanied by deep sorrow. They are all blended together like binaries.” Abinash wishes not to be enticed by boons any further and bids God a goodbye.

The narrator of Dipti Ranjan Pattanaik’s In Search of Ms. Adela Quested is puzzled to receive an Email from Emma Gallagher, an internationally acclaimed writer two years after sending one to her. He intended to write a post-colonial version of the novel A Passage to India and shared the idea for the first time with her at a workshop on creative writing. Emma invited the writer to come to England and see the women from close quarters before venturing into the writing of the novel. The narrator, while in England, spends two days with Emma. He learnt that Emma, despite being beautiful and middle aged and possessing unimaginable wealth, power and fame was terribly lonely and desperate. The narrator also noticed that all the women whom he met there were struggling for their existence. ‘To be desperate for the extrasensory’ was something rare there. The narrator is surprised to find Emma and some of her writer friends indulging in ‘provocative talks,’ ‘vulgar queries’ and ‘furtive smiles’. However, he was happy that he could retain his worth as someone whose behavior didn’t abandon his life’s philosophy and Emma’s respect for someone who represented India remained unaffected.

Like Ranjan Pradhan’s The Duma, Paramita Satapathy’s Wild Jasmine also presents a conflict. Here the conflict is between the traditional ways of thinking of the inhabitants of a remote village and the so-called ‘modernity’. Ratan Singh, the supervisor of a road-construction company informs Rina, an Anganwadi worker, that once the huge concrete road is constructed, there would be a great change in the economy of the area. The inhabitants will get gas, electricity, grocery etc. easily. Their place will have schools, colleges, hospitals and doctors. On the other hand, the locals suspect that they are going to blast the mountains and start mining in the area. “Why should they abandon their traditional ways and embrace something modern?” the locals ask. They claim that they feel pleasure and pain the same way; are affected by summer and winter the same as the so-called moderns. The day Rina overhears the conversation between the overseer and his friends, the real character of the ‘moderns’ is revealed. She sends his brother and his friends to take revenge on Ratan Singh and his people for having tried to cheat them.

Smita in Adyasha Das’s The Road Inwards is terribly disturbed when she encounters her deceased husband’s shadow everywhere in the lonely house at Kasauli. She even ‘unmistakably heard footsteps on the stairs’ which sounded like the ones that Ambuj made when he was alive. When Ambuj’s sudden exit from her life is as lethal as death, she wonders why she is filled with ‘such an uncontrollable fear at these signs of his return’. The conflict of wanting Ambuj on one hand yet hesitant to face his formless presence on the other tortures her. Smita remembers the advice of her mother, ‘…fear was myth, an illusion of the mind…when the mind would be weak, fear would enlarge its size…the longest road is inwards, leading deep within yourself.’ This provides a resolution to her mental conflict.

Manas Panda’s Hide and Seek is a pathetic account of how a simple child’s game can often turn disastrous. It was Lulu’s turn to count and Kunu’s turn to hide. The excitement of the game continues till they both try to befool each other. However, Lulu’s feelings of joy turns into concern as the little boy eludes her search and remains out of her reach. She starts suspecting that in his attempt to emerge victorious, he might have run outside the gate. Finally, Kunu’s dead body is discovered, in a sitting posture, from inside the fridge. His wide open eyes reflect his victory over his sister but it comes with a great price—his death.

Ranjan Pradhan’s The Duma presents a clash—the clash between tradition and modernity. The clash arises out of the construction of a dam over river Indrabati. The dam, once completed, was going to submerge large tracts of land and a number of Adivasi villages. The government had announced compensation, constructed a rehabilitation colony, and taken every step for the resettlement of the would-be displaced. But the problem was— how could an adivasi abandon the land of his fathers and forefathers? Displacement meant separation from their Dangar (hill), their Dumakudi (graveyard), their Dumas (spirits), their Baali kudia (place of worship), the seats of Bhima debata, goddess Durnimata etc. Buddu Jani, the oldest member of the community, pooh-poohs the idea of compensation by the government and wonders, “How dare these people obstruct the flow of running water of our rivers, streams and springs? It is the property of water to flow downwards with a murmuring sound. It is a great sin to prevent its flow.” The arguments put forth by Robert Domb, a convert Christian in favour of their departure cannot convince Buddu Jani. Robert says, “…the new village to which we will be shifted has electric lights. The school building has been completed and the village has been connected by a pucca road. Two tube wells have been dug up… our children will be admitted into school and shall be civilized through education.” For the older adivasis it’s a question of abandoning their tradition. The Dumas are scared of electric lights; they would never agree to stay with them. In that case, who would protect them, their village, and their corn fields? Finally Buddu Jani is bodily lifted by some youngsters into the truck carrying them to the rehabilitation village but his soul remains with the salap tree in the erstwhile village.

Kshetrabasi Naik’s Bonded Labour is the story of Maguni Bariha, a farmer. Maguni’s exploitation and torture, first in the hands of a local landlord and subsequently in the hands of the brick-kiln officials in a neighbouring state, are delineated here. Drought, flood and famine for three consecutive years force Maguni to release his oxen and leave for Andhra Pradesh to work in a brick-kiln. Inclement weather, lack of adequate food, unhygienic conditions and slogging from morning till night take their toll on Maguni. Without medicines and proper care, his youngest child dies. There’s no escape from the hands of the contractor and his people. When his other son suffers from high fever, Maguni and his wife Kaincha rush to the contractor and plead for some money. The contractor has a condition—“Kaincha would have to share his bed for a night”. With her son’s fever refusing to subside and all options to obtain money for treatment exhausted unsuccessfully, Kaincha surrenders to the contractor’s demands. Devastated Kaincha jumps into the fire of the kiln the next day. Her son succumbs to the fever. Only Maguni is left—alone and devastated.

Rabinarayan Dash’s Mother’s Home is a graphic account of a selfless, hardworking and determined mother who braves all odds to save her family from disintegration. Instead of being perturbed by the untimely demise of her husband, she pulls herself together and works tirelessly to steady her family-boat and finally, saves it from sinking. When everyone in the neighbourhood feared that “The Tripathy family was going to be obliterated; that the five children had been orphaned” she took to herself the act of restoration. “Everybody feared that she might end her life” but a lady with an undaunted spirit she “surprised everybody by steadying herself” and by readying “herself to bear the burden”. Besides, she plays a pivotal role keeping the members together by exercising an astounding control on each of them. “Sometimes Siddharth wondered how mother could keep the snakes and mongooses together; where from she had procured the magic-root that mesmerized everyone.” It’s only when she gets bed-ridden that the same children, whom she had fondly grown at the cost of her sweat and blood, display how selfish they can be. All of them become worried when she simply “refuses to die”. They conveniently forget their responsibilities but are more interested in her gold ornaments that they can share only after her death. The final action of the second son reaffirms our faith in humanity. He says, “The house belongs to her. She will live here till she rots and her body mixes with the soil” and gets ready to take care of her.

The narrator in Sreekanta Barik’s Passionate Tune is fascinated to hear heart-rending and pathetic tunes on a flute on a Pousha evening. Upon enquiry, he discovers a weak and emaciated man playing the flute. “The soulful lamentations of a human being expressed through the tune of the flute” attracts him. When acquaintance grows, the man lays bare his heart. Makaru lived a blissful life with his pregnant wife in a slum. One day, on being directed by the government, some officials arrive to vacate the slum. The slum-dwellers visit the collector, ministers and leaders but nobody comes to their rescue. When policemen arrive a few days later, some slum-dwellers charge at them with lathis. A good fight ensues. In order to evade backlash by policemen, Makaru tries to escape with his wife. She falls on the road; her stomach is bumped. She is rushed to hospital where she gives birth to a dead child and dies. The flute, whose tune fascinated Sumati when she was alive, becomes the medium through which Makaru expressed his grief and gets peace.

As the reader traverses from one world to another that these stories portray, one would easily discover that no two characters are the same. The experience that each protagonist goes through in life is also a different one. The protagonists display normal human emotions like pride, helplessness, compassion, love, devotion, remorse, vengeance, betrayal, exploitation, conflict, deceit, feelings of loneliness and many more in the course of life’s journey. Besides, life teaches everybody its own lessons.

If the stories fascinate you, kindly don’t forget to write to us. If your expectations are betrayed, kindly don’t forget to criticize us.

Wish you all a happy reading.

Manoranjan Mishra

manoranjanmishra74@gmail.com

Sample Story From The Book –

The Living God

Santanu Kumar Acharya

Translated by Supriya Kar

What kind of a house is this, daddy? The five-year-old Miskun asked his daddy. “This isn’t a house, my boy, but a place of worship. God dwells here. We Hindus call it a temple. This temple was built in the seventh century AD—very ancient.”

How strange, how very novel this information seemed to Miskun. Though he was only five, his information base was quite strong. He was born at Glastonbury in Connecticut, America. Mark Twain’s house-museum was a shout away from his home. He had visited Mark Twain’s place a number of times with his daddy and mommy. He intimately knew Mark Twain’s character, Huckleberry Finn. Miskun also knew Henry Thoreau, Emerson, and other writers. Their house-museums were all around Boston. However, visiting a temple was altogether a new experience for Miskun. He was amazed to see such a structure. Who knew what thoughts crossed his mind while witnessing that peculiar kind of a house called ‘temple’ from inside the car while his soft, tiny hands clasped his daddy’s stretched hands that reached for him from the backseat?

Seema and Bijan Senapati, Miskun’s parents, sat in the backseat of the car. Miskun sat in the front seat. His maternal uncle, Sidharth, a high-ranked officer in the Indian Civil Service, drove the car.

Sidharth was very fond of his nephew, Miskun. His only sister, Seema was always dear to him. Sidharth knew Bijan long before he married his sister. Bijan was a brilliant student during his time, but he had a rather naïve worldly point of view. In those days, a number of students chose to study arts after the intermediate level, but Bijan preferred science. He had topped the examination and graduated in physics. Again, instead of going for a Master’s degree in physics, he enrolled himself in a bachelor’s degree in engineering. In the meantime, Sidharth had completed his Master ’s degree and sat for the Indian Civil Service examination. His first attempt was a failure, but he got through the second time. Bijan joined as a Junior Engineer at a government office on completing engineering.

The same year, he got married to Seema. Before finalizing the marriage, Sidharth’s father had sought his son’s opinion: “What do you think of this young man, Sidhu?”

“He’s very brilliant, but, on the whole, a dolt.” Sidharth had offered his certificate.

“A dolt?” Sidharth’s father looked at his son, rather puzzled.

“What else is he if he isn’t sharp enough to guess which direction the winds blew in? He should have realized by pursuing a second bachelor ’s degree, he would lag behind his contemporaries. Take my case—by the time he became an Executive Engineer with all his brilliance, I’d already been in a superior position of Commissioner-cum-Secretary in his department.” Sidharth had laughed.

“But, he has been first-class-first throughout his career— a gold medalist in Engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology!” Sidharth’s father, Sankar sir, a retired high school headmaster, did not commend his son’s vanity. He was rather adamant on forming this matrimonial alliance, so Seema’s wedding was fixed with Bijan. Sidharth had no option but to accept it. Though he loved his sister dearly, he looked down upon Bijan. Whenever he met Bijan, he had the same feeling of disdain. Ah, poor Bijan!

However, life changed for Bijan Senapati in no time—he went to America for higher studies. He completed his doctoral degree at the world-renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology and joined General Motors. That was the year Miskun was born. And this was the first time in five years Seema and Bijan had come to visit India with Miskun. It was Sidharth’s responsibility to take them to Puri and Konark on a trip. He had set a travel plan to send them to far-off places with the driver and car provided by his office but chose to drive them to nearby tourist spots in the town first. While taking the car out of his garage, Sidharth asked his sister, “Where would you like to go? Have you ever visited our famous Odisha State Archaeological Museum, here in the capital city of Bhubaneswar?”

In fact, neither Seema nor Bijan ever had an opportunity to visit any of the famous sites of Bhubaneswar, the capital city of their native state Odisha. They knew the city was dotted with marvelous, ancient temples, which were declared as world heritage sites. They often came across a description of these temples in coffee table books on art.

They got into the car and took their seats. Sidharth drove the car out into the street.

“Brother, are there really a hundred thousand temples here in Bhubaneswar?” Seema asked on the way to Old Town, where most of the ancient and famous temples were situated—this part of the city always witnessed a flow of tourists from all over the world round the year.

“Don’t you know this is known as the city of temples?” Sidharth laughed. “Come, let me show you the oldest temple in the city.”

They passed by the museum and drove towards Kedar Gouri road, which led to a cluster of temples. Sidharth halted the car near Parsurameswar temple: “Look, there,” he pointed at the beautifully preserved ancient shrine of Shiva, built in the famed archaeological style of Odisha, and declared, “The glory of Odisha! The Parsurameswar temple—it was built in the seventh century A.D.”

At that time, the little boy who was sitting by his uncle’s side in the front seat was heard asking his dad, “What kind of a house is this, daddy?

When Miskun heard ‘seventh century A.D.’ from his daddy’s mouth, a similar expression came to his mind: “Mark Twain was born in nineteenth-century A.D., wasn’t he, daddy?”

‘Yes, yes, Mark Twain was born a hundred years ago. You’re right, my boy! But do you know how old this temple is! Thirteen hundred years old, one thousand and three hundred years! Just imagine…!”

“Ho, ho, ho”—Sidharth laughed out loud—he did not quite like the idea of asking a five-year-old to imagine thirteen hundred years. He wanted to change the discussion.

“Bijan! You have got elections this year in the USA? Who do you think will win? Will Bush come to power? How good are the chances of the Republicans?”

“No, no, no,” Miskun protested immediately, “Dukakis, Michael Dukakis will win. The Republicans have got a poor chance.”

Sidharth was left astounded—he looked at his five-year-old nephew from top to bottom, smiled and turned to his sister.

Seema returned a smile in the manner of the Americans. She looked very charming. She had not looked so attractive when she was in India. Those days, she hardly knew how to smile . The daughter of a high-school teacher, she was not as bright as her brother, Sidharth. Somehow, she plodded through till graduation. Then she got married to Bijan, who hailed from a poor family. He was in a less lucrative job than her brother. At times, Seema would feel upset about it. She would ask her brother in private, “Seriously, brother? How could father decide to tie me with such a blockhead?” Tears streamed down her cheeks. Sidharth would comfort his sister, “You don’t know, dear! Bijan was considered a prodigy in our time. We could hardly hold a candle to him. Had he opted for political science, he would have topped the civil service list. Never mind. He’s so brilliant.”

“Bullshit!” Seema had twisted her face away in anger when this alliance was finalized by her father. Her face usually wore a dry, melancholic look. That was then. Now a smile played at the corner of her lips. She had picked up the typical manner in which the Americans smiled with their thirty-two teeth out on display. It was another matter of surprise for Sidharth that Seema’s personality could develop so much in a matter of just a few years.

Unraveling her personae a little more, Seema remarked, “Brother, children are born smart in America. Miskun can operate a computer if you get him one now.”

Sidharth was elated to learn about his nephew’s talent. After hanging around temples such as Kedar Gouri, Mukteswar, Rajarani and finally the Lingaraj temple, they set out to visit Odisha State Archaeological Museum. While his uncle turned his car towards the huge iron gates of the Museum, Miskun asked, ‘Uncle, is it a science museum? In Boston,we have a number of such museums…”

“No, no, my boy! “His dad quipped, “This is an archaeological museum. Old sculptures thousands of years old are preserved here. Come, we’ll see.”

“Yeah, you’ll see very old images of gods and goddesses here in this huge mansion! But alas! All of them have died long back!” said Sidharth, laughing heartily.

“Dead gods!”—Miskun was taken aback as though he had seen a ghost. He simply could not believe what his maternal uncle said. “The gods have died?” He asked in Odia heavy with an American accent, “Is this a cemetery for gods, uncle?”

Sidharth laughed indulgently. Bijan explained to Sidharth in good humor, “In America, being an atheist has connotations with being a Communist. The boy might be shocked suspecting his uncle was a Communist!”

“Yes, yes, I’m a confirmed Communist. If you remember, I was a member of A.I.S.F during college days. You might have seen me then. I ran in the college union presidency election. I still believe in socialism,” Sidharth grew serious on this note.

The museum tour took quite some time. They inspected most of the important archaeological sections where galleries of images of Hindu, Buddhist and Jain deities from classical to Baroque periods were put on display. All along, while introducing the deities to his sister and brother-in-law, Sidharth would remark—“Do you know the real worth of these dead gods in international markets? Billions, if not trillions, in American dollar!”

Their museum visit was coming to an end. Miskun lingered on and continued to ask all sorts of questions—“Daddy, which god was this? Uncle, was this god a very cruel god? How terrible he looks! Mommy, that’s a god or a goddess? Were they all alive indeed?” Miskun was given appropriate answers as far as possible. His daddy would say, “This god is known as Abalokiteswar— he’s Padmapani—they belonged to the tenth century.”

“Look, look here, this god is called Mahakala. He’s a ferocious god. He killed and devoured everyone. Oh, how terrifying he looks!” His uncle added.

While gazing at the image of goddess Tara, Miskun’s mother mulled over something and remarked: “Ah, how beautiful! Brother, do you know how much such an image would cost? None of these would be less than ten thousand dollars. If you sold this entire museum, say, to Americans, they would pay billions and billions of dollars and lift these images, even all your ancient temples and restore all of them in America.”

Sidharth gave a smile. “That would be wonderful! Poverty would get eradicated from India in a day. You do one thing—start an antique business, Seema! I believe the eradication of poverty would remain a dream until these dead gods are not removed from this country. Such foolishness! Millions and millions of rupees lie in the form of stone sculptors, and yet we’re poor!” He shared his observation.

Miskun listened to everything attentively.

The museum tour now over, they were supposed to head to the hotel Kalinga Ashok for lunch. They had been roaming around for a long time and were tired. It was slightly past lunch time. All of them sat in the car. Miskun took his seat as before in the front, but he was no longer his talkative self. Perhaps, he was hungry. He looked drowsy.

The car stopped at the hotel’s portico. They got down the car and entered the lounge. Sidharth was a known face at the hotel. The manager received them warmly. A few of Sidharth’s acquaintances and friends were present too. In the lobby, Sidharth, Bijan, and Seema sat amidst the gathering of friends. All of them seemed to forgot about Miskun for a while.

As a waiter came and informed Sidharth that the food was ready to be served, everyone rose to their feet. They realized that Miskun was nowhere in sight.

Seema grew restless. Bijan got alarmed and ran around the hotel to check if there was any swimming pool or water body inside its premise. Miskun always ran to the swimming pool whenever they went to a hotel in America. Filled with anxiety, Sidharth shouted at the hotel staff—“Find the boy! I’ll get you sacked, all of you…”

A frantic search ensued. The boy was here a moment ago— how did he disappear suddenly? Was it a case of kidnapping? Could this be possible at such a renowned hotel?

Bijan was struck by a memory. He told Seema, “If you recall, a similar incident had happened earlier. While roaming around Mark Twain’s house-museum, the boy had gone missing, hadn’t he?”

Seema felt flabbergasted. In a choked voice she said—“Yeah, I’m at a loss. Could he, by any chance, go back to the museum? Let’s rush there!”

Bijan and Sidharth followed Seema. Only a wide road lay between the premises of Hotel Kalinga Ashok and the museum. Before Seema and Bijan could rush into the museum through the gate, Sidharth’s people had jumped off its boundary wall to get inside. They searched desperately all over the museum premises, inside and outside, but there was no sign of Miskun.

Seema could no longer keep herself in check. She started crying loudly like a rustic woman. Last time, events had turned out in a similar manner at Mark Twain’s house-museum. The police were informed when Miskun went missing—the police thoroughly searched the three-storeyed building of the Mark Twain museum, but in vain. Helpless in the wake of such a crisis, Seema could no longer control herself and had let out a loud cry which seemed to have shaken the huge mansion of Mark Twain. She had howled uncontrollably—“Oh my God! Mark Twain, please give my child back!”

Strangely, this invocation to Mark Twain seemed to have worked. After a while, the police discovered Miskun at what seemed an improbable place inside the museum. Apparently, the child had fallen asleep on one of the couches inside Mark Twain’s library, a book in hand—Tom Sawyer. Perhaps, he had dozed off while reading and the book covered his face. What was astonishing was someone had covered him with an overcoat, perhaps fearing the boy might catch a cold. That overcoat belonged to none other than Mark Twain; that very overcoat, which visitors saw hanging as a museum piece in his wardrobe in another room.

Bijan and Seema had felt overwhelmed discovering Miskun in that state. The police had expressed surprise, too. They had not been able to solve that mystery. How could the overcoat be taken from the wardrobe in another room and placed on the child sleeping peacefully in the library? Was it the job of Mark Twain’s ghost?

They had harboured such a suspicion, but no one had asked that unpleasant question directly to the boy.

However, today, in this outlandish environment of an archaeological museum, where the halls were packed with sculptures of gods and goddesses, Seema could take it no more. She began wailing out the names of all gods and goddesses like a village woman beseeching their favor to return her child wherever they might have hidden him. She approached a huge sculpture of Lord Buddha. The information provided underneath said ‘Abalokiteswar.’ She kneeled herself down before the huge granite sculpture and prayed aloud— “Oh Lord Abalokiteswar! Please give me my child back. Otherwise, I’ll end my life here in front of you…Miskun, my child….”

It seemed as though another supernatural incident had occurred in Miskun’s life. Miskun was sitting in a lotus posture behind a Buddha sculpture adjacent to a wall. Probably shaken out of his meditative state by his mother’s call, he responded nonchalantly, “I’m here, Mommy.”

Everyone rushed towards the huge room, from where Miskun’s voice was heard . He was still sitting in the lotus position. His eyes were half-closed as though he was awakening from a trance.

Sidharth stretched out his hands at Miskun to hug him, but Miskun pushed them away: “I’m not a dead god! No, you can’t sell me—you can’t sell me!” He yelled at his father and moved away. What was he saying? Everyone whispered, but no one had a clue. Seema gathered her son into her arms and broke into tears: “No, no, no one would sell you, my child. You’re my living God! Oh, Lord Buddha! Lord Abalokiteswar! Mother Tara, bless my child with a million years….” She sobbed through her words like any mother in India.

Original Odia: Chalanti Thakura

Additional information

| Weight | 0.45 kg |

|---|

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.